The concept of hip resurfacing is not new. In fact, hip resurfacing implants were used as early as the 1950s and 1960s as surgeons tried very hard to reduce the amount of bone that was removed at the time of joint replacement; the idea being both to preserve bone for any subsequent revision operations that might be required, particularly in young patients, but also to try and effect a more physiological reconstruction of the hip. Unfortunately, the results of historical resurfacing using less durable bearing surfaces such as polyethylene, Teflon™, ceramic and metal bearing surfaces were not always reliable.

In the 1990s there was a resurgence in interest and development of hip resurfacing, specifically surrounding metal-metal hip resurfacing, both in America and indeed in the UK, centred in Birmingham.

The Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR as we now know it) was first implanted in 1997.

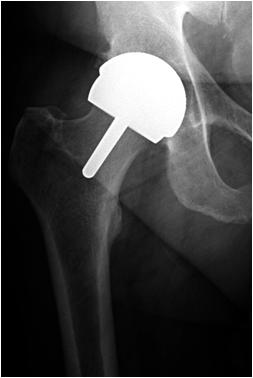

As can be seen in on this x-ray, the basic concept of the procedure is that instead of removing the top part of the femur and implanting a stem into the shaft of the bone, the top of the bone is re-shaped to allow a spherical metal implant fixed with bone cement, to replace the areas of the femur that were damaged by osteoarthritis. This, therefore, preserves the entire proximal femoral shaft for any further planned procedure. Simultaneously, an uncemented acetabular component is positioned carefully into the pelvis using a similar technique to that used in a total hip replacement. This results in a ‘metal against metal’ bearing surface.

The theoretical benefits of hip resurfacing are to reduce the amount of bone removed at the time of surgery, to facilitate any further procedure required during the patient’s lifetime and to effect a more physiological loading of the patient’s proximal femur. Using this larger head size (more similar to the normal head of the femur) has been shown to reduce the rate of dislocation of the hip when compared to a more traditional total hip replacement. This, alongside the expectation that the metal on metal (MoM) bearing would prove more wear-resistant in young and more active patients, provides the potential for the patient to be able to return to, and enjoy, more active recreational and occupational activities after surgery. Some of these activities might be a concern following more traditional hip replacement. This ability to return to more active sports has been demonstrated with a number of high-level athletes successfully able to return to sport after hip resurfacing surgery for severe arthritis.

The procedure itself is sometimes thought of as a ‘lesser’ option. Certainly it could be viewed as being less invasive with regard to the bony skeleton. In my opinion, however, hip resurfacing is a more extensive procedure involving a more extensive surgical approach and requiring an increased amount of soft tissue release around the hip. This is as a consequence of the fact that with the femoral head and neck preserved, the surgeon still has to mobilise the femur sufficiently to gain good access to the socket. (With a total hip replacement the ‘top’ of the femur has already been removed.)

It is particularly important to get good access to the socket to ensure that the component is placed in perfect alignment in the pelvis. A slightly increased amount of soft tissue release is therefore required. All of the above can, in my experience, lead to slightly increased discomfort and swelling acutely following hip resurfacing surgery.

Hip resurfacing in my practice is aimed at the younger and more active patient group. Typically male patients are in their forties and fifties. Femoral neck fracture, most commonly occurring within the first six months, is one of the more common complications following this procedure. As the technique relies on the patient’s own proximal femoral head and neck, the operation can only be considered in patients with good bone quality in the proximal femur. If there is any concern about bone quality, one would be less likely to consider hip resurfacing. Sometimes we will plan additional scans to investigate bone quality further before a decision is taken regarding the suitability for hip resurfacing.

Over the years, I have had extensive experience with hip resurfacing, using the BHR and carrying out my first procedure in 2000. I travelled to Birmingham and was taught to perform the procedure by the developing surgeon, Mr Derek McMinn. My results with the BHR have been good. My experience, over more than 20 years, initially with the BHR and more recently with the only other MoM hip resurfacing implant available, the Adept®, has been similar to the reported literature surrounding the implant from both designer surgeon and indeed national registers in the UK and elsewhere, such as the Australian Joint Registry.

Unfortunately, the results of resurfacing have not been as good in some patient groups as in others. Specifically, the results have not been as good in women and in patients with smaller hips for reasons that we do not completely understand. The importance of accurate component orientation is now more widely recognised. Thus, optimal surgical exposure and technique is crucial to obtain good results with this procedure.

Similarly, the results of some hip resurfacing implants have not been as good as others. As detailed above, the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR) and more recently the Adept are the only MoM hip resurfacing implants that I use.

Additional Complications of Hip Resurfacing Surgery

Complications of hip resurfacing surgery are similar to those detailed elsewhere relating to total hip replacement surgery. In addition to all those detailed, however, there has also been shown to be a slight increase in the early complication rate in hip resurfacing when compared to more traditional hip replacements.

The most common complication following hip resurfacing surgery is femoral neck fracture. Fracture can occur at any time but is most common within the first six months with an increased risk within the first three months following surgery. Fracture will typically occur secondary to trauma but can be related to poor bone quality and also can occur if there is damage sustained to the femoral neck at the time of the procedure. Typically, however, this would be identified at the time of the procedure with an intraoperative decision then taken to convert to a total hip replacement at that stage.

Fractures of the femur can occur during and after all hip replacement surgery and it is important to appreciate that femoral neck fracture is uncommon after hip resurfacing. The management of a fracture will depend on the nature of the injury, the time since surgery, the location of the fracture relative to the femoral neck and to the component and how well the metal-metal bearing is functioning at the time the fracture occurs. While historically following femoral neck fracture a stemmed implant with a large metal head was used to articulate with the existing acetabular component, at this stage femoral neck fracture is likely to require revision of the hip resurfacing to a total hip replacement. This procedure would involve removal of the acetabular component alongside a procedure on the femoral side to exchange the fractured femoral neck and insert a stemmed femoral component, typically resulting functionally in a primary-type hip replacement. In the absence of any associated metal on metal wear process resulting in soft tissue damage, the outcome following revision of hip resurfacing for fracture to a more traditional total hip replacement is typically good. One would expect the patient to return to a very good level of functional activities following this procedure.

While a slight increase in revision rate has been reported globally with hip resurfacing when compared to total hip replacement, it is important to appreciate that not all hip resurfacing devices were the same. Very few metal-on-metal hip resurfacing devices are still in use. Importantly, the results of the BHR and Adept MoM hip resurfacing implants, when inserted carefully, in correct alignment and in suitably-chosen patients, have been very good both in terms of longevity and specifically in terms of functional outcome.

Metal-metal hip resurfacing, using either the Adept® (MatOrtho) or the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR, Smith & Nephew) is now performed only in men and indeed is limited to patients with a femoral head size templated to be 48 to 50 mm and above. The best outcomes have been reported from the Registry and surgeon series results with this device in that particular patient group.

Other factors surrounding hip resurfacing are that the procedure itself requires a slightly increased surgical exposure involving a slight increase in the amount of soft tissue that is released around the hip. This can result in an increase in swelling and discomfort acutely following the surgery. This would typically settle quickly and, in my experience, patients who have had hip resurfacing and who have had hip replacement look very similar at around six weeks from the operation as they start to rehabilitate more definitively.

The issues that surround abnormal wear reactions to metal-metal debris are detailed elsewhere in the website.

Previously, I did use the BHR in female patients and indeed patients with slightly smaller hips and my own personal experience in these patients remained good. While I have had to revise a small number of patients for a number of indications, including where they had developed an abnormal reaction to metal debris, the number of patients who have had BHRs within my practice who have then required revision is small. As detailed above, at this stage my use of metal-metal hip resurfacing is limited.

Overall, the patient and the surgeon need to be clear that the potential benefits of using hip resurfacing technique (bone stock preservation on the femoral side, more physiological loading of the proximal femur, reduced dislocation rate and the possibility of enhanced physical activity following surgery) with the slight increased risks of hip resurfacing over a more traditional hip replacement, would outweigh those theoretical risks.

For all these reasons, the number of patients in which the hip resurfacing procedure is truly indicated remains, in my opinion, relatively small.